Optimising our staple food for social equality.

Our mission at The Sourdough School is to optimise our staple food for social equality.

The Baking as Lifestyle Medicine (BALM) Protocol has been developed over two decades. It is an evidence-based protocol that lays out the out the rules governing every level of the bread making process including baking, eating, and sharing bread, and baked goods to provide a path forward explicitly aimed at social and political change in the way we approach bread and baked goods.

Systems change programme of prescribing bread as lifestyle medicine is about revolutionising the bread-making process at every level- from soil to slice. The rules governing this are laid out in our Baking As Lifestyle Medicine protocol. Comprising seven principles and reflecting over 20 years of research, our BALM protocol is built upon the six pillars of lifestyle medicine and guides everything we do here at the school. This is holistic, person-centred branch of medicine that seeks to prevent, manage and reverse lifestyle diseases by tackling the root lifestyle choices behind their development. Collectively, the pillar are known as the six pillars of lifestyle medicine, a key part of the “Lifestyle Medicine Principles” as laid out by the British Society Of Lifestyle Medicine

Challenging power asymmetries in the food system

I’d always felt injustices in the food system acutely. The understanding on the dynamics of inequalities in the food system meant that I was actively engaged in transforming the system from as early as I can remember. Age 13, I set up and ran a sponsored walk that my entire school participated in. We raised hundreds of pounds to get food to famine areas in Ethiopia.

I knew from my research university about the environmental impacts of industrialised food, and the manipulation of our decision making from the studies we were conducting on decision making at the point of sale. I was also acutely aware of how food poverty exacerbated class inequalities, not just in the UK but globally.

I committed to activism once I had seem first hand how one person can disrupt an entire industry

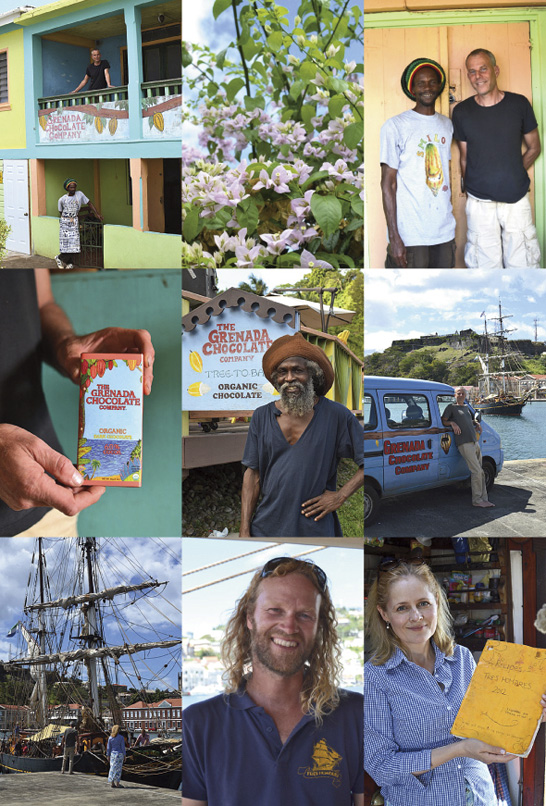

I’d always been an activist, but I felt as through I didn’t have any idea where to start. The trigger for really understanding that the way I approached bread was as a systems change came in early 2013, when I visited the anarchist, entrepreneur, activist and systems challenger Mott Green. He was a Jewish New York businessman and had founded the Grenada Chocolate Company. I went out to New York as part of BBC Radio 4’s The Food Programme to do a story on him. My Food Programme stories were always based around fermentation. As a contributor, I got extraordinary access to people who were at the heart of producing food.

Mott was originally born David Friedman, and he had been the valedictorian of his class on Staten Island. He went to university in Pennsylvania, but he didn’t finish his course. In the winter of 1988, on his way into a lecture at university, he went to say ‘good morning’ to someone with whom he regularly conversed, a man who was homeless (Mott often took a cup of coffee to him on the way in and out of the university). Mott discovered that he had frozen to death in the night. It was a moment that changed Mott’s future. He fundamentally questioned the structure of a society in which people who had socio-economic disadvantage could find themselves in such a situation. This was a city of great wealth, and yet people were freezing to death on the street. He dropped out of university and joined what was essentially a group of dissidents.

He disagreed with the capitalist structure of society that created such extreme levels of poverty. Mott took up squatting, and moved from building to building as part of this group. Instead of graduating with his engineering degree, he jumped into the commercial system, which he realised had fundamentally failed the people he cared about. He broke into buildings in New York and Pennsylvania and repaired the heating systems, so that people who were homeless no longer had to risk freezing to death at night because they didn’t have access to, essentially, the baseline of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: warmth. Mott did this successfully for a number of years, and the group became involved in other dissident activities including skip-diving for food waste and challenging the system.

Mott had a deep connection to Grenada, having spent many holidays there in his childhood. He went back out to Grenada in about 1995. He wanted to step away from society. He told me that he felt he needed a break from the system; that, just by living in the system, you were obliged to participate in systemic demise and destruction. So he moved to Grenada and built a hut by a stream, in an effort to reconnect with himself and step out of the system. While he was there, he realised that there was chocolate – cocoa – and it was being left to rot on the floor. The Grenadian ladies were making ‘cocoa tea’; they were, essentially, chocolate-making. He saw and connected the dots between the cocoa that was being left to rot, the price that was being paid to the farmers and the broken socio-economic system within Grenada. He saw that the cocoa that was being supplied to the industrial chocolate industry was bought on the commodities market, which kept prices so low that farmers were trapped in a poverty loop to such an extent that they use forced labour and slavery (including children) in rural areas of cocoa-producing countries such as the Cote d’Ivoire.

Here was a cash crop that was lying and rotting on the floor, because the system of food production that commoditised the chocolate wasn’t paying the farmers fairly for their crop, and so they were losing interest. But in addition, the agricultural system itself was being challenged, with a system that failed to reward food production through sustainable farming practices. People were coming away from the land, and abandoning the systems that connected the food, the soil and environmentalism to how we eat. There was a disconnect between the cocoa and the fermentation of the cocoa.

Mott wanted to change this, so he started a chocolate company. But this wasn’t just any chocolate company. Instead, it was quite possibly the most radical chocolate company that had ever been seen. It doesn’t even begin to compare to any others. The systems and processes that he put into this revolutionary vision became known as ‘tree to bar’ (not ‘bean to bar’ but ‘tree’ to bar).

Motts’s absolute dedication to demonstrating systems change within the process of his business model was the truth that he was living and breathing. Every breath, every heartbeat, was true to his values. What was clear to me as I connected his practice to my own principles was that he had made a decision, consciously or unconsciously: he was living his vision without compromise. And the cost? He was known as ‘the Barefoot Chocolatier’ because he had so little interest in consumerism; he had one pair of shoes for when he visited the UK, and it was cold, because shoes were of no importance in his world.

I could see this understanding and acknowledgement of defiance – positive defiance – in action. He created food that, when consumers understood what they were consuming, transformed them into activists making conscious decisions to proactively support dissidence and systems change through consumption. And it set every molecule in my being on fire.

I described to Mott and Arjen an acute feeling I’d had that I did not belong: a sense of not fitting in, of being ‘beautifully eccentric’, and a feeling that my knowledge was not enough. I had what in psychological terms is known as cognitive dissonance, and just teaching middle-class baking in rural Northamptonshire was totally inconsistent with my thoughts and beliefs.

Values –

ONTOLOGY

So, as I was sitting on a boat with self-described anarchists Arjen and Mott, I talked about how the bread-making system was broken, and how frustrated I was. Instead of agreeing and sympathising with me, they challenged me and asked me what I was doing to fix it. In that moment, I was actually pretty taken aback. This wasn’t what I had expected. They both looked at me, as I replied somewhat defensively, ‘ I don’t have a chocolate factory or a brigantine.’

‘What do you have, then?’ asked Mott.

This was the key moment. As I replied, ‘I have a Sourdough School,’ I immediately understood what I needed to do in order to live according to my principles. I saw the structure and understood that I needed to rebuild the system with the evidence embedded within it that would create change. I knew that what I had seem from Mott and Arjen also needed to happen within the bread-making system, and I understood that my value system of believing in human rights and being an environmentalist was the underlying structure of this change. In that same moment, I realised that whilst I had been looking for someone to give me the answer, I already had the solution. I just hadn’t realised that I needed to consciously build a systems change programme.

What Mott and Arjen had shown me was that instead of my belief system being a weakness, it was my motivation: my true north, The model that Mott had built was the example that I still use as a framework. His concept was real and engaged others in the real world. My Botanical Blend Flours, for example, were created on the basis that ‘if you can’t find it, then invent it’. At one point, when Mott couldn’t ethically source what he needed – cocoa butter – he invented a system using his engineering skills. Mott was a prime example of a transdisciplinary practitioner. He welded car jacks into the fabric of the building, putting a structural system in place that allowed 200,000psi pressure in order to create cocoa butter that stayed within the values and principles of the production system vision he had. This was another example of him using his engineering knowledge to create a systems change.

Mott engineered and recrafted machinery, such as a winnowing machine (winnowing is a particular part of the chocolate-making process), building a chocolate factory from the ground up. The machines that he needed had not even been invented. In order to process the chocolate from tree to bar, he not only had to gather the cocoa beans and ferment them (which was radical in its own right) but also to control that fermentation, in the same way as you do with sourdough, in order to control the flavour. This fermentation and the microbial transformation of the beans by lactic acid bacteria is where the link comes in between the sourdough and Mott’s chocolate.

This process was literally a systems challenge at every point of the process, and on every level. Like the homogenous wheat in the bread-making system, cocoa beans are a commodity crop. The cocoa used in mass-produced commercial bars was so poor-quality – and in certain cases, in other interviews I did with chocolate-makers, they found cocoa covered in rat faeces, insects and unpleasantness. The commercial, cheap, low-cocoa-content chocolate being sold to the mass market was having to (in most instances) disguise some of the unpleasant flavour notes of its fermentation by the addition of vanilla in the chocolate bar. And here was Mott, connecting the microbial transaction between the soil systems, the fermentation and the insects that would pollinate the cocoa flowers. It was magical.

In the same way that certain lactic acid bacteria strains found on some starters produce higher levels of acidity,* Mott recognised that insects and the role they played were integral to the process. The insects and the soil systems in which the insects lived were an integral part of the system that created the chocolate. The midges that lived in the forest would only survive and thrive as part of the forest when the full ecosystem of the forest was left intact, without deforestation, without pesticides or herbicides, without human interference. These were the insects that would then transport their microbial inoculation of lactic acid bacteria. They were part of a system that facilitated the fermentation that created the flavours and transformative process that produced one of the most exquisite, award-winning chocolates that we have ever been privileged enough to eat.

Mott did not compromise. It was never enough to produce just the chocolate – the zero-carbon-emissions chocolate that he had designed. Anarchists attract other anarchists; we are our own tribe. He introduced me to one of my best friends, Captain Arjen van der Veen of the Tres Hombres.

Arjen likewise had recognised that the transportation system is deeply and fundamentally flawed (and the flaws are invisible). He saw that the consumerist system – where our value is in momentary value – was the same system that was allowing huge tankers to belt out filthy, dirty crude oil with no regulation, creating more environmental damage than all the SUVs in Europe.

With his unique understanding of maritime systems and systems change, Arjen and his colleagues – almost in the same way as Mott built his factory – had built Tres Hombres, a 32-metre brigantine – a pirate ship. It was crewed by a group of dissident environmentalists who would (and still do) transport fairtrade cargo around the world with zero carbon emissions. Here was the completion of the circle, making the zero-carbon chocolate truly ‘tree to bar’, and paying fair prices to the farmers. We transported and moved 50,000 bars of hand-labelled and hand-dated chocolate from Grenada and shipped them back to Europe, where we were met with an army of environmentalists who delivered the chocolate by bicycle to the shops. This was a game-changer.

Despite influencing bakers, the impact of a flawed food system is far more complex than simply getting enthusiastic artisan bakers to buy in to making heatlhier bread. The following I was gaining was almost cult-like. Sourdough is not just a process. It is a way of understanding, and, as such, once people have converted there is no going back.

Why?

Mass-produced bread is a nutritionally devoid, ultra-processed food, made with adulterated ingredients and processes. This is what is provided to the population as our most basic food. This bread contributes significantly to all Western illnesses, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. My aim is to address this social injustice as part of The Sourdough School Systems Change Programme. This programme has formed part of a cohesive solution to changing the paradigm of bread: reframing bread, not just as a way to feed people, but as a way to nourish us as preventative medicine that can support both physical and mental health.

When I reflect on my own practice and draw myself back down to my value system, the core values in which I believe and the attachment that I have to our planet, to our home – I am an environmentalist.

This is reflected in the way I approach my work and my bread protocol. Because in essence, the connection to the soil, the practices, the way that we farm, the Botanical Blends, the flowers – all of these things are echoed in the connection between the sourdough starter and the way that fermentation facilitates bioavailability of key nutrients. These key nutrients are integral to nourishing the gut microbiome and producing the metabolites required for healthy brain function.

This is the foundation upon which our mental health is built: having the raw materials with which to manufacture the chemicals, and neural transmitters that are needed for healthy cognition. That healthy cognition comes back to the way we feel, and the way we feel impacts the way we live our lives: in a mindful way, in a connected way. And I don’t mean mindful in the sense of just being in the moment; I mean it in the sense connection and understanding. Our being – our mental health and who we are – is intrinsically linked to the health of our planet. We cannot afford to break those connections, because as we degenerate and devolve, gut microbes in our gut become less diverse, and we are less able to function. As understanding in the scientific community has progressed, we have started to really understand that the gut microbiome is the key to both physical and mental health.

When you couple that with evolutionary theory and you look at how we have evolved symbiotically with this microbial system – the soil system, the food system, the fermentation, our core nourishment, being connected to the prebiotic, the probiotic, the postbiotic (of which the fermentation process is an integral part) – and you put bread at the heart of the fermentation (the heart of the connected system), then everything that I have done – the entire system from start to finish – involves the BALM Protocol. All of this living life through enquiry has enabled me to recreate a system without compromise. The trick now is not just to get people to buy in to the system, but to make sure that in every action, throughout every part of my practice, I empower people to replicate that system. It’s in the replication of a system that has been built without compromise that we can make meaningful impact. And this, I believe, will positively impact the way we live through our daily practices, reconnecting us to the planet. It is about doing. Until the moment you act, it’s all just an idea. Sharing my recipes on the @SourdoughClub website isn’t just about teaching people to make bread.