The Project Proposal

THE SOURDOUGH SCHOOL PILOT STUDY

The effect of sourdough Fermentation on the Gut microbiome and mood

Background

Wheat represents one of the world’s major sources of food with up to 300 million tons consumed annually, and bread is highly consumed worldwide (Watson R.R, 2014). Cereal fermentations has changed significantly in the past 150 years, and industrially produced fast fermented bread has become part of the staple diet. Despite this, there is an increasing body of evidence that long slow fermented sourdough bread, produced with a symbiotic live culture of lactic acid bacteria and wild yeast, have potential health (Gobbetti et al., 2019). Moreover, eating wholegrains is associated with many health benefits and epidemiological findings show that consumption of wholegrains have a protective effect against several metabolic diseases, which in part has been attributed to the phenolic compounds and dietary fibres in cereal (Vitaglione, Napolitano and Fogliano, 2008a). The bioavailability of fibre in breads can remarkably be influenced by fermentation. The long slow fermentation of bread, using lactic acids bacteria and wild yeast, significantly increased bioavailability of key nutrients including polyphenols and minerals to the microbes in the gut (Anson et al., 2009; Ripari, Bai and Gänzle, 2019; García-Mantrana et al., 2016).

In recent years gut microbiota has experienced an extraordinary level of intense investigation (Blaser, 2014). Interactions between dietary factors, the gut microbiome, and host metabolism are increasingly shown to be important for maintaining both physical and mental health. (Cani and Delzenne, 2007). From a systematic review, 39 out of 42 studies showed an increase in microbiota diversity and/or abundance following intact cereal fibre consumption (Jefferson and Adolphus, 2019)(Jefferson and Adolphus, 2019). Moreover, in a recent study on rats, the authors provided evidence that the consumption of sourdough-leavened bread vs yeasted bread had the potential to appreciably change the gut microbiota of rats, and in turn affect the metabolic functions of two key phyla, Bacteroides and Clostridium (Abbondio et al., 2019). On the other hand, a study comparing the effects of whole-grain sourdough bread against industrial white bread did not observe any significant changes in the gut microbial balance or composition. However, this may have probably been due to the short consumption period (1 week) (Korem et al., 2017b).

Increased levels of dietary fibre have been shown to increase the levels of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the gut, which are considered to be anti-inflammatory and are required for optimal health (Vitaglione, Napolitano and Fogliano, 2008b). This suggests that an increase in the bioavailability of fibre via fermentation may modulate the composition of the gut and increase SCFAs.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 322 million people, which is around 4.4% of the global population, are currently suffering with depression (GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators, 2019). Accumulating data indicates that changes in gut microbiota can have a positive effect on mood, via the so called gut-brain axis, interacting with the neural, endocrine and immune pathways and so potentially influences brain function, mood and behavior (Wang and Kasper, 2014; Foster, Rinaman and Cryan, 2017) . For instance, it has been reported that certain bacterial species were found to inhibit inflammation and decrease cortisol levels resulting in an amelioration of the symptoms of anxiety and depression (Cheng et al., 2019).

Due to the paucity of studies on sourdough bread on gut microbiome and mood in humans, and their encouraging results, there is the need to further investigate into this promising area of research.

The majority of these studies lack sourdough process information, including the timings of the bread-making process and desirable dough temperature (the DDT), and the specific microbes in the starter, which have an effect on the nutritional profile of the sourdough and available nutrients. Indeed, these factors affect the breakdown of nutrients, phytonutrients, bioactive peptides and minerals, the bioavailability of fibres, and the levels of prebiotics such as resistant starch in the sourdough, all of which could have an impact on the gut microbial composition and balance. (Gänzle and Zheng, 2019). This contribution of sourdough process information will be addressed in this study.

The research Question.

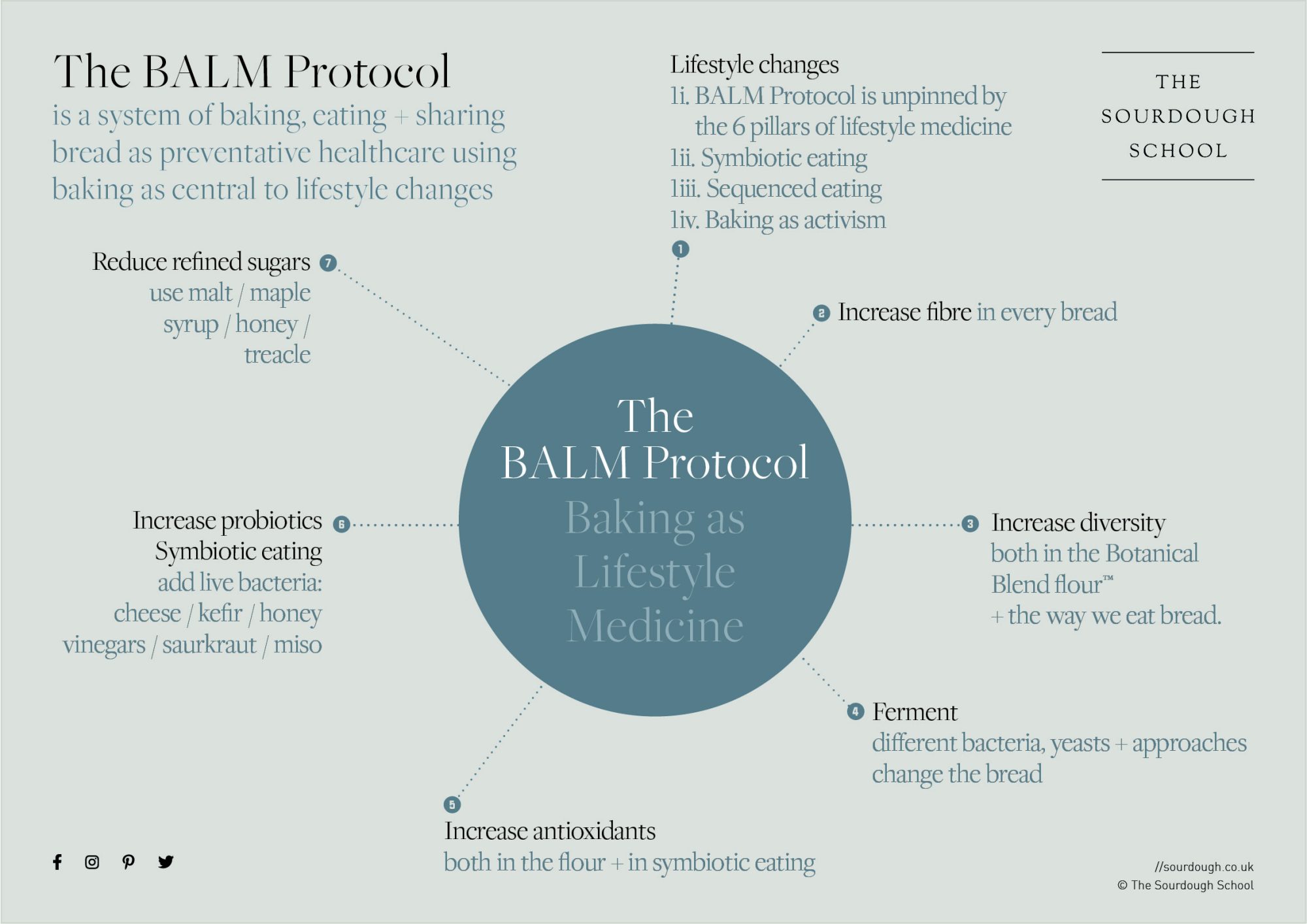

How does the BALM protocol, when applied over a ten-week period, affect changes in mood states and changes in the balance of the gut microbiome and to what extent can alterations in the gut microbiome composition explain any observed mood changes or impact any self-reported symptoms?

Study hypothesis

We hypothesise that baking and eating sourdough bread according to the BALM protocol would result in changes in microbiome balance and that the combination of making bread and eating higher levels of diverse fermented fibre could potentially influence the balance and levels of gut-derived metabolites, such as SCFA, which may in turn influence mood and self-reported symptoms related to increasing fibre and potentially might relate to changes in the balance of the bacteria in the gut.

Study design

A parallel dietary intervention study designed with ten healthy participants over 18 years of age and not on current medications will be carried out. People who have recently used (less than one month) probiotic or high-fibre supplements, and antibiotics (currently or in the last 3 months), have chronic conditions, such as IBS, diabetes, clinically diagnosed mental disorders, or celiac disease, will be excluded from the study. During a period of 10 weeks, participants bake, eat and share bread according to the BLAM protocol. Before and after the 10 week intervention, participants will collect a stool sample. Stool samples will be sent directly to Atlas Biomed where they will undergo 16s RNA sequencing to profile the gut microbiome.

Participants will be asked to record their mood at baseline (before the start of the trial) and continue to do so on a daily basis for the 10 week period using a score of 1 – 10 for their mood, based on The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing scale (WEMWBS).

Sourdough supplementation

Before starting the trial, all the participants will receive all the materials and equipment that they need in order to bake for 10 weeks. Volunteers will have the choice to either attend a free online support and follow The Sweet Sourdough School book at the Sourdough School (https://www.sourdough.co.uk/) where a professional baker will teach them how to bake bread or access the online video course to learn to make the bread. Full baking training and support will be given to the participant at The Sourdough School. Each participant will act as their own control, with the first gut test results being compared to the last tests and scoring their own unique health symptoms.

Data collection methods

Before and after the 10-week intervention participants will self-report how they feel and their symptoms. They will collect a stool sample using a certified kit provided by Atlas Biomed. Stool samples will be sent directly to Atlas Biomed, where they will undergo 16s RNA sequencing to profile the gut microbiome, including metrics of microbiome diversity and gut-derived metabolites such as short chain fatty acids. In addition, the bacterial content of the starter culture will be known as it will be supplied by Puratos. Faecal samples will be collected during the week before the start and at the last day of the 10 week intervention. Participants’ mood will be measured using a simple scale based on The Warwick-Edinburgh a Mental Wellbeing scale ( WEMWBS) that was developed to enable the monitoring of mental wellbeing in the general population and to evaluate projects, programmes and policies which aim to improve mental wellbeing. Participant will be asked to follow the diet and report weekly on their symptoms and mood for the duration of the study.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis will be completed via IBM SPSS. Data will be initially examined for normality and homogeneity of variance prior to using parametric tests. If the appropriate conditions are not met, the appropriate non-parametric tests will be chosen. P-values P<0.05 will be considered statistically significant. Interviews with the Sourdough School team will feedback to individuals their results and discuss outcomes in recorded interviews.

Application Process & Consent form

Social Media, including blog posts, Instagram, Twitter & Facebook will be used to attract applicants and a local village newsletter, in Pitsford. Slightly modified versions (based on the media used) of the following text will be used:

“Take Part in a Sourdough Study

It’s time to better understand the bread we eat and how it affects us. We are exploring how eating long slow fermented wholegrain sourdough might modulate our gut microbiome and affect mood positively.

We are currently recruiting volunteers for a groundbreaking pilot study to gather data and generate a better answer for everyone to the questions: Does baking according to BALM Protocol benefit gut health? And if so does this impact the way we feel?

So what does getting involved mean?

You will need to sign-up to see whether you are suitable for this study. You will ask to provide stool samples that we can use to understand the bacteria in your gut better and keep a food and mood diary over 10 weeks.

To register your interest in our study and find out more visit our website https://www.sourdough.co.uk/sourdough-research/.

#sourdough #personalisednutrition #personalizednutrition #guthealth #nutritionresearchUK #nutritionisascience postprandialresponse #gutmicrobiome sourdoughschool”

Participants who respond to a social media post or newsletter will be directed to a participant information sheet. This form will contain all the information explained in lay terms details about the study and what is required to participate. Form (https://www.sourdough.co.uk/sourdough-research/)

Should the participant decide to register an interest then they will be screened for exclusion criteria by asking them to fill in an application form. (https://www.sourdough.co.uk/research-participation-consent-form/ ). Should the participant meet the inclusion criteria for the study they will receive a consent form which will be provided in electronic form for each participant, and an email that reminds them of the participant information sheet. Evidence of a completion of informed consent will be obtained before the research starts. We will use a digital verification software, such as HelloSign.com or Docusign.com.

Ethical issues

The proposed study will comply with the Data Protection Act and standard University Good Scientific Practice guidelines. All contact details, electronic consent forms and electronic data will be stored in a password protected hard drive-in locked offices at the sourdough school East Bank House, Moulton Road, Pitsford, Northampton, NN69AU. Participants will be offered an ID code which will be used instead of their name, and if requested any identifiable information will be removed. Participants will be offered a consent form to allow their test results and feedback video to be used on The Sourdough School website as case studies for training for students.

All raw and analysed data will be kept for 5 years. Data collected for this project is consensually shared with other individuals not officially involved in the research project. Additional emphasis and clarity will be made on the time involved, we make clear how data will be analysed and protected, and the participants have freedom to withdraw consent at any time. The Sourdough School is GDPR compliant.

The stool samples will be collected by the participants and directly sent to Atlas Biomed to be anlaysed, therefore this procedure does not require a Human Tissue license.

Risks to participants

The study design implies very low risk to the participant.

- Sourdough and baking components are certified food products and are sold over the counter.

- The stool samples will be processed by CE IVD-certified device according to its intended purpose but a gut testing company.

- An increase of fibre and/or probiotics in diet may, in some cases, cause flatulence or bloating; in this case, a participant might consider skipping the next meal of sourdough or completely stopping the participation at his/her own convenience.

- Participants will need to bake and follow basic health and safety in their kitchen whilst making recipes

REFERENCES

Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Statistics—2016 Edition; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-statistical-books/-/KS-FK-16-001.

Watson R.R., Preedy V.R., Zibadi S. Wheat and Rice in Disease Prevention and Health: Benefits, Risks and Mechanisms of Whole Grains in health Promotion. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2014

ABBONDIO, M. et al. (2019) Fecal Metaproteomic Analysis Reveals Unique Changes of the Gut Microbiome Functions After Consumption of Sourdough Carasau Bread. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, pp. 1733.

ANSON, N.M. et al. (2009) Bioprocessing of wheat bran improves in vitro bioaccessibility and colonic metabolism of phenolic compounds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 57 (14), pp. 6148-6155.

BLASER, M.J. (2014) The microbiome revolution. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 124 (10), pp. 4162-4165.

CANI, P.D. and DELZENNE, N.M. (2007) Gut microflora as a target for energy and metabolic homeostasis. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 10 (6), pp. 729-734.

CHENG, L.et al. (2019) Psychobiotics in mental health, neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1021949819300158.

CODA, R., RIZZELLO, C.G. and GOBBETTI, M. (2010) Use of sourdough fermentation and pseudo-cereals and leguminous flours for the making of a functional bread enriched of ?-aminobutyric acid (GABA)Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016816050900659X.

DE VOS, W.M. and DE VOS, E.A. (2012) Role of the intestinal microbiome in health and disease: from correlation to causation. Nutrition Reviews, 70 Suppl 1, pp. 45.

FOSTER, J.A., RINAMAN, L. and CRYAN, J.F. (2017) Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiology of Stress, 7, pp. 124-136.

GÄNZLE, M.G. and ZHENG, J. (2019) Lifestyles of sourdough lactobacilli – Do they matter for microbial ecology and bread quality? Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168160518305427.

GARCÍA-MANTRANA, I.et al. (2016) Expression of bifidobacterial phytases in Lactobacillus casei and their application in a food model of whole-grain sourdough bread Available from:http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168160515301173.

GBD 2017 DIET COLLABORATORS (2019) Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet (London, England), 393 (10184), pp. 1958-1972.

GOBBETTI, M. et al. (2019) Novel insights on the functional/nutritional features of the sourdough fermentation. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 302, pp. 103-113.

HERVERT-HERNÁNDEZ, D.et al. (2009) Stimulatory role of grape pomace polyphenols on Lactobacillus acidophilus growth Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168160509004954.

JEFFERSON, A. and ADOLPHUS, K. (2019) The Effects of Intact Cereal Grain Fibers, Including Wheat Bran on the Gut Microbiota Composition of Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 6, pp. 33.

RIPARI, V., BAI, Y. and GÄNZLE, M.G. (2019) Metabolism of phenolic acids in whole wheat and rye malt sourdoughs Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0740002018303368.

VITAGLIONE, P., NAPOLITANO, A. and FOGLIANO, V. (2008a) Cereal dietary fibre: a natural functional ingredient to deliver phenolic compounds into the gut Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924224408000447.

VITAGLIONE, P., NAPOLITANO, A. and FOGLIANO, V. (2008b) Cereal dietary fibre: a natural functional ingredient to deliver phenolic compounds into the gut Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924224408000447.

WANG, Y. and KASPER, L.H. (2014) The role of microbiome in central nervous system disorders Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889159113006004.

YANO, J.M. et al. (2015) Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell, 161 (2), pp. 264-276.

YUNES, R.A. et al. (2016) GABA production and structure of gadB/gadC genes in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains from human microbiota. Anaerobe, 42, pp. 197-204.